Its Role in Improving Mine Drainage and Transport

In the 18th century the two foremost impediments to making collieries profitable were flooding and transport.

At this time, the accepted way of draining shallow mines was to use men or horses to draw up buckets of water. A somewhat more advanced method was to use a horse gin. An alternative method, if the coal seam (known as a mine) was at a higher level than the surrounding ground, was to drive a sough (tunnel) from the lower ground to the mine.

Additionally, the road system in the country was also inadequate and poorly maintained. Transport was by horse and cart or even by packhorse and it was expensive. If the coal seams happened to be in an area where there was a navigable river then this could be used for transport. Often this was not the case but when one was available then it was subject to the vagaries of weather, floods, water shortage and silting up of the channel.

Wet Earth Colliery and James Brindley's Hydraulic Pumping System

In c.1740 John Heathcote, a landowner in the Irwell Valley, Lancashire, endeavoured to sink the first deep colliery in the area at Clifton but it persistently flooded and

Matthew Fletcher (c.1733-24 Aug 1808), a member of an influential local mining family, was brought in to advise on how to solve the flooding problem. It seems that he had little success and in due course the

mine closed. In 1750, Heathcote called in the renowned engineer and millwright, James Brindley (1716-72), to advise on how best to prevent flooding.

James Brindley.

Heathcote was impressed with Brindley's abilities and he thereupon appointed him to put into practice a solution to the flooding problem at Wet Earth. It took Brindley two years to survey the land and design an appropriate pumping system. Heathcote accepted Brindley's proposals in 1752 and the go-ahead was granted for work to commence. It took Brindley another four years, until 1756, to complete the work.

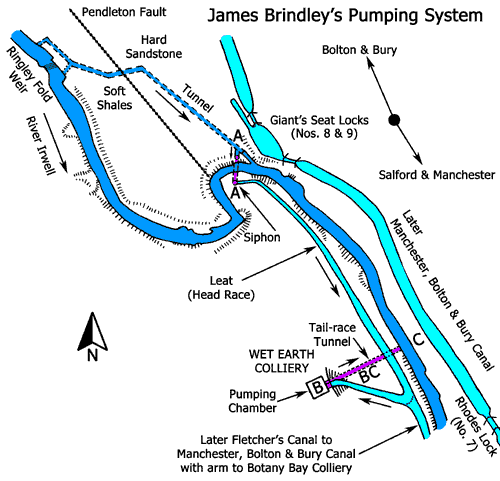

Brindley's solution was to use the river Irwell to provide power to pump water from the bottom of the shaft. Wet Earth Colliery was located close to the south bank of the river and upstream, by the hamlet of Ringley Fold; the river begins a loop nearly half-a-mile wide. He resolved to build a weir across the river near Ringley Fold, the purpose of which was to impound water and increase the head of water available to power a waterwheel. Above the weir, on the north bank of the river, he drove a tunnel some 800-yards long across the loop as far as Giant's Seat. To begin with, it was driven through shale, which required it to be brick lined. The works then struck the Pendleton Fault where it entered sandstone and from thereon it was unlined. Just below the weir a short side tunnel was driven to the river bank for flush-out purposes.

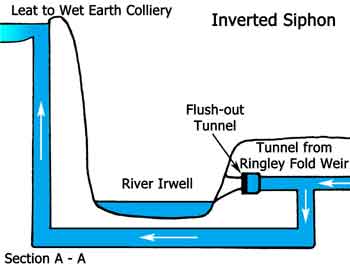

The tunnel arrived at the river by Giant's Seat where a vertical shaft was sunk to a depth below that of the bed of the river Irwell, as well as one more flush-out tunnel to the river bank. Opposite this shaft, on the south bank of the river, a second vertical shaft was sunk to the same level as the first tunnel. The two vertical shafts were then connected together by driving a 220-foot long horizontal tunnel below the bed of the river. In this way, the two vertical shafts and the horizontal tunnel formed an inverted siphon.

From the top of the southern shaft an open leat (head race) was cut to a point close to Wet Earth Colliery where it turned sharply westwards. It then entered the hillside by a short tunnel that accessed the pumping chamber where the pit shaft was located. In this chamber, Brindley installed an overshot waterwheel to drive a pumpjack (or nodding donkey). Water pumped from the mine shaft and spent water from the waterwheel then discharged down a tail-race tunnel into the river Irwell.

Brindley's ingenious system was successful and Matthew Fletcher became the owner of Wet Earth Colliery. Afterwards, he sank a new shaft at Wet Earth, known as Gal Pit, which was some 159-foot deep and 13 feet in diameter. This shaft reached down as far as the Doe seam of coal. The name of the pit comes from Galloway pony, the traditional name for pit ponies or Galloways.

To summarise; water from above Ringley Fold Weir flowed along a tunnel for some 800 yards, passed below the river by way of the inverted siphon and rose to the open leat on the south side of the river. The leat then conveyed the water to the pumping chamber where it powered the waterwheel that, in turn, drove the pumpjack that lifted water out of the mine. Drain water and spent water from the waterwheel then discharged into the river Irwell via the tail-race tunnel. The head of water from the top of Ringley Fold Weir to the pumping chamber was 35 feet.

Following the positive result of this project, James Brindley became known as the 'man who made water run uphill' because of the inverted siphon below the river Irwell. It was this project that confirmed him as the leading engineer of the day and in retrospect he was arguably the first civil engineer of the Industrial Revolution. The Wet Earth project showed that he had the ability to conceive, plan and bring to a successful conclusion a major undertaking, while at the same time training others to carry on with the work while he attended to other tasks.

By 1760, Fletcher had sunk another shaft one mile east of Wet Earth Colliery, known as Botany Bay Colliery. Simultaneously, he extended Brindley's leat for this distance where he installed a second waterwheel but this one was used to wind coal up the shaft.

Brindley's waterwheel worked continuously until 1867 when it was replaced by a water turbine. This worked until 1924 when a steam-driven pump replaced it and this worked until 1928 when the colliery closed. Thus Brindley's waterwheel worked for 111 years; the water turbine for 57 years and the steam-driven pump for four years. Closure of the colliery did not spell the end for Brindley's tunnel, siphon and leat. These continued to supply water for industrial purposes until 1960 when the site of the tunnel was used for Ringley Fold Sewage Treatment Works. After that, Ringley Fold Weir was used to supply cooling water to Kearsley Power Station.

Wet Earth Colliery and Fletcher's Canal

By the 1790s, Matthew Fletcher was the Chairman of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation and a Committeeman of the Manchester, Bolton and Bury Canal Company. He was also the Principal Engineer of the latter company.

In 1790-91 he widened and deepened the leat between Wet Earth and Botany Bay Collieries and extended it eastwards, in preparation for making a head-on junction with the proposed Manchester, Bolton and Bury Canal (MB&BC). The purpose of this was to enable him to convey coal from his mines, while still retaining the original function of Brindley's leat. This isolated canal became known as Fletcher's Canal and on the hypothesis that it was provided with a number of coal boats then initially it could only have been used to carry coal to a wharf adjoining a suitable road and/or tramway.

Please use the Scrollbar to pan over the map of Fletcher's Canal and Wet Earth Colliery.

Although the MB&BC was opened between Rhodes Lock and Salford in 1796, there was still no connection between Fletcher's Canal and the MB&BC in 1799. The delay in making the connection was brought about by these issues:

Mill owners by the river Irwell had only agreed to the construction of the MB&BC after strict conditions had been written into its Act to limit the amount of water that the canal could take from the river further upstream. This meant that it was essential that no water from the MB&BC should enter Fletcher's Canal.

It seems that in anticipation of making a connection, Matthew Fletcher had built a lock in his canal, which was located about 220 yards from the proposed head-on junction with the MB&BC but its fall was found to be too great for the water level in the MB&BC when it opened. The Derbyshire engineer, Benjamin Outram, who was advising the canal company at the time, recommended the construction of a second lock in Fletcher's Canal with a small rise. Apparently, his recommendation received the approval of both the canal committee and the mill owners but it was not acted upon. Instead, the original lock seems to have been enlarged to create a chamber 90-foot long by 21-foot wide, with a fall of 20 inches towards the MB&BC, which therefore always gained water. This lock could accommodate three narrow boats side-by-side.

In the event, Fletcher's Canal was connected to the MB&BC in c.1801. When completed, it was 1½-miles long and it joined the MB&BC at Clifton Aqueduct. Its course was parallel to the MB&BC but on the opposite bank of the river Irwell.

There was a towpath throughout the length of Fletcher's Canal and to connect this to the towpath of the MB&BC, a junction side bridge was built at the southern end of Clifton Aqueduct, this being known as Pack Saddle Bridge. The lock was located about 220 yards from Clifton Aqueduct alongside Pilkington's Tile Works. In the manner of lock construction, there was a weir at the head of the lock and a by-wash. This ensured that the MB&BC was always gaining water from Fletcher's Canal. The entrance of the canal arm to Botany Bay Colliery was on the north west corner of the works. This arm was approximately 380 yards long. Just beyond the entrance to the arm, a footbridge crossed Fletcher's Canal. At about 1,147 yards from Clifton Aqueduct a change bridge was built and the towpath changed from the north side to the south side of the canal. At the point where Fletcher's Canal made a head-on junction with James Brindley's original leat, it turned westwards for about 190 yards to its terminus at Wet Earth Colliery. In this section a skew railway bridge and a travelling crane crossed the canal.

Underground canals were driven from Fletcher's Canal into Wet Earth, Botany Bay and Spindle Point Collieries after the Worsley example (the Duke of Bridgewater's mines) albeit on a more modest scale. At Wet Earth a plan of the Doe coal seam workings, dated 1860, shows 'an old boat level' some 1,000-yards long running to the boundary of the Clifton Estate. At Botany Bay the level seems to have run for about two miles to Spindle Point Colliery. However, the entrance to this was destroyed when the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company built their line. Similarly, there is archaeological evidence that an underground boat level extended from the downcast shaft at Wet Earth to other nearby collieries.

In 1805 a new shaft was sunk at Wet Earth and this one had a steam-winding engine. By the mid 19th century this was reaching the rich Trencherbone seam. Other seams to be worked included Doe, Cannel, Hell Hole (or Victoria), Five Quarters, Plodder and Crombouke. In the 1860s, yet another shaft was sunk.

Matthew Fletcher died in 1808 and his nephew, Ellis Fletcher inherited the Clifton Estate. On his death the estate passed to his son Jacob Fletcher Fletcher and eventually to his daughter, Charlotte Anne Fletcher.

Ultimately the waterwheel at Botany Bay ceased winding coal but Fletcher's Canal continued to be used for drainage purposes. In 1831 an Act empowered the MB&BC Company to convert their canal into a railway with a rail branch to the collieries. This Act prohibited Fletcher's Canal from being used as a railway line but it did give mine owners free carriage on the proposed railway branch. Nevertheless, all this came to nothing when this Act was repealed in 1832 but the second Act did remove the prohibition on Fletcher's canal being converted into a railway line in order to return to the status quo.

Following the death of Jacob Fletcher Fletcher in 1857, trustees managed the collieries (his daughter was only 12-years old). In 1864/5, their collieries and Fletcher's Canal were leased to Joseph & Josiah Evans and they brought in their nephews, Charles and Edward Pilkington, sons of glassmaker Richard Pilkington, as managers. In 1867 the Clifton and Kersley Coal Co was founded by Edward and Alfred Pilkington and they took over the local collieries owned by the Fletcher family. The Pilkington family owned the Pilkington Tile and Pottery Company at Clifton and Pilkington Brothers Ltd at St Helens, Lancashire. In 1885 the Clifton and Kersley Coal Co Ltd was incorporated (Company No. 21449). In 1929 this company was acquired by Manchester Collieries Ltd but it was not dissolved until 1948 after the coal industry had been nationalised.

Eventually, a railway branch was built from Clifton Junction that ran, first to Botany Bay and then on to Wet Earth, which was known as the Wet Earth Railway.

In 1880 serious mining subsidence occurred on Fletcher's Canal that caused it to be closed for about nine months while repairs were affected and in 1892 Botany Bay Colliery closed.

In 1896 Wet Earth Colliery had a workforce of 304 underground and 104 surface workers. Records show that in 1905 Fletcher's Canal carried 142,905 tons of coal. Of this total, 32,369 tons were carried down the MB&BC to Salford and Manchester, while 110,536 tons were both loaded and discharged on Fletcher's Canal, that is, carried from mine to railway. The revenue from tolls was given as £1,551. However, these figures must be compared and contrasted with the same set of Royal Commission statistics that give the tonnage leaving Fletcher's Canal for the MB&BC as 67,348 tons.

Wet Earth Colliery remained open until 1928, as it was then no longer economic, following which Fletcher's Canal ceased to be used to carry coal. The only traffic on Fletcher's Canal was then clay and feldspar carried the short distance to the works of the Pilkington Tile and Pottery Company. Fletcher's Canal closed in 1935 when it ceased to be used to carry materials to Pilkington's works. The remains of Wet Earth Colliery are now set in Clifton Country Park, Clifton House Rd, Clifton, Salford, M27 6NG.

Further Reading

De Salis, Henry Rodolph, 1904. Bradshaw's Canals and Navigable Canals of England and Wales. Fleet Street, London: Henry Blacklock & Co Ltd.

Hadfield, George and Biddle, Gordon, 1970. The Canals of North West England. 2 Vols. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.