Canal companies levied tolls on the weight and type of cargo carried and all new boats had to be indexed (calibrated) before they were allowed into service. Once a boat had been correctly indexed and it was in service, the procedure for obtaining the weight of cargo it was carrying was called gauging. There were slightly different methods of indexing boats around the canal network but one commonly used was as follows:

A new boat was floated into a special dock equipped with iron weights and cranes for the purpose of lifting these weights into the cargo hold of the boat. The first step was to establish the datum, which was the position of the freeboard when the boat was empty. To do this, a gauging rod was used to carefully measure the freeboard at four known points on the gunwales of the boat. These points were at one point each side near the bows and one point each side near the stern and their locations were marked, typically by small copper plates.

Next, weights to a value of four tons were picked up by the cranes and evenly distributed along the length of the cargo hold and once more the freeboard was measured with the gauging rod at the four points. This procedure was then repeated in increments of four tons, normally up to a total of 28 tons for a narrow boat.

The weights were then removed from the hold and the average freeboard reading for each 4-ton increment was calculated and subdivided into one-ton and half-ton readings. A copper or cast-iron gauge plate, bearing a reference number and sometimes the the year of gauging, was then affixed to the boat. These details were then added to the master gauging sheet for the boat, copies of which were circulated to toll collectors who all possessed gauging rods identical to the one used to index the boat.

When in service, a laden boat could not commence its journey until it had been gauged. The toll clerk would first measure the freeboard (dry inches) at the four known points. He would then add these measurements together and divide the total by four to obtain the average freeboard for the whole boat. He would then record the average freeboard, gauge reference number, type of cargo being carried and the distance it was to be carried. Reference was then made to the copy of the boat's gauging sheet from which the weight of cargo being carried could be read off. A permit was then issued to the person in charge of the boat who was then free to leave.

If the person in charge of the boat also happened to be its owner then he could pay the toll collector directly before leaving. If he was not the owner, then an invoice would be sent to the company who owned the boat.

Bye-laws concerning gauge plates and permits were strict. It was an offence to deface a gauge plate or to navigate without one. Permits were variously known as pass notes, bills of lading or tickets and it was an offence to navigate without one. It was an offence not to show a permit to a toll collector, lock keeper or other authorised person on demand and it was an offence to falsify a permit. Finally, it was an offence to commence unloading a boat without first handing the permit to the wharfinger, or his clerk, in charge of the wharf. Canal companies were empowered to fine anyone caught breaking bye-laws and in the 1870s a typical fine for each of these offences was £5.

The above method of indexing and gauging boats was in use until c.1963 and another method was as follows:

A new boat would have vertical grooves cut into the hull at one point each side near the bows, one point each side amidships and one point each side near the stern. A lath was then put into each groove and lightly nailed in place. With the boat in the dock, the first step was to establish the datum, which was the location of the freeboard when the boat was empty. This was done by marking the position of the water line on each of the six laths.

Next, weights to a value of four tons were picked up and evenly distributed along the length of the cargo hold. Typically, to make up four tons, twelve 600 lb weights and four 440 lb weights were placed in the hold:

Marks were then made on the six laths at the water line to record the freeboard with 4 tons in the cargo hold.

This procedure was then repeated in increments of four tons, normally up to a total of 28 tons for a narrow boat.

The weights and the six laths were then removed, the latter being used to make permanent index strips. The markings on each lath were subdivided into one-ton and half-ton markings. Each lath was then taken and placed at the side of a copper index strip, which was 1¼ inches wide x about 2 feet 8 inches long. The markings on the lath were then transferred onto the copper strip and stamped in place, together with numbers representing each one-ton increment. On completion of this work, the six copper strips were fastened to the hull in the grooves already present. At the top of each strip a small copper gauge plate was attached to the hull bearing a reference number and the year when the boat was indexed.

When the boat was in service, the toll clerk would first note the position of the water line on each of the six strips and record the corresponding weight to the nearest half-ton. The average of the six readings would then be calculated to give an accurate reading of the weight of cargo being carried. The rest of the procedure was then similar to that described above.

Collecting Tolls on the Peak Forest Canal

It seems that the gauging system used by the Peak Forest Canal Company was similar to the second of the two methods described above. Each boat was identified by a plate attached to it bearing the

words 'The Peak Forest Canal Company' and a number. This plate was accompanied by six index points, that is, on each side of the stem and stern and on the middle of each side.

In July 1829 the Peak Forest Canal Company combined the various instructions then in use for gauging and marking boats for the collection of tolls into one regulation:

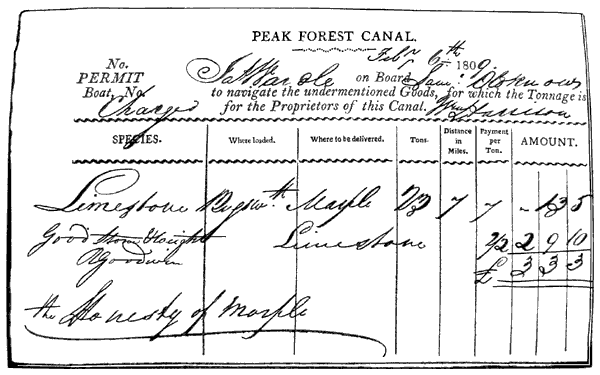

Example of a Peak Forest Canal Permit

The Peak Forest Canal permit shown above was issued on the 6 Feb 1809. It permitted John Wardle on board Samuel Oldknow's Boat to carry 23 tons of limestone from Bugsworth Canal Basin to Marple, a distance of 7 miles. It was signed for by William Harrison at Bugsworth Basin. It is uncertain whether William Harrison was the wharfinger at this time or the toll clerk.

Signed for at Marple Lime Works by the clerk, R Goodwin, who commented that it was 'Good Stone & Weight'.

Canal Milestones and Mileposts

Britain’s canals were an essential part of the industrial revolution and it was necessary for canal companies and boatmen to accurately know how far boats had travelled along canals.

These distances then formed the basis of toll charges.

Canal Acts of Parliament often required that milestones or mileposts should be placed at mile-long intervals along the canals. Numerous canals also marked half and quarter miles and cast-iron mileposts sometimes bore the name of the canal’s terminal.

|

|

0 Milestone. This milestone is located at Ashton Junction at the start of the Peak Forest Canal where it connects with the Ashton Canal at the southern end of the Tame Aqueduct in Dukinfield. |

5½ milestone. |

|

|

8 Milestone. This is the only milestone to be carved with the details. The details on all the other milestones were painted on. It once read, '8 miles to Ashton' but 'Ashton' was removed at the outbreak of World War Two for security reasons. |

9 milestone. |

|

Boundary Marker. Canal Companies marked the boundaries of the land that they owned where they considered it to be necessary. |

Tolls charged for stone carried on the Peak Forest Canal

These fragmentary records are for stone carried from Bugsworth Canal Basin to Marple Limeworks between the 22 Apr 1800 and 26 May 1800.

Each record represents one boat journey over a distance of seven miles.

Limestone

This stone was from the quarries around Dove Holes Dale and it was transported to Bugsworth Canal Basin on the Peak Forest Tramway.

| Limestone | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date (1800) | Quantity (tons) | Date (1800) | Quantity (tons) |

| 22 Apr | 25 | 13 May | 25 |

| 22 Apr | 25 | 14 May | 23 |

| 23 Apr | 24½ | 14 May | 24 |

| 23 Apr | 24½ | 15 May | 23 |

| 24 Apr | 24 | 16 May | 25 |

| 8 May | 23 | 17 May | 24 |

| 9 May | 23 | 26 May | 22 |

| 13 May | 24 | Total: | 383 |

The total cost of 383 tons of limestone at Marple Lime Works was £36 14s 1d. This was based on 11d per ton for the limestone and 12d per ton for carrying it.

Road Stone (Gritstone)

This stone was quarried at Crist Quarry adjoining the village of Bugsworth.

| Road Stone (Gritstone) | Date (1800) | Quantity (tons) |

|---|---|

| 10 May | 11 |

| 10 May | 13½ |

| Total: | 24½ |

The total cost of the road stone (gritstone) at Marple Lime Works was £3 8s 4¾d. This was based on 26½d per ton for quarrying, cutting and dressing the road stone and 7d per ton for carrying it.