Coal tub with iron body

Motties (coal tub identification tokens)

When tubs full of coal reached the surface (bank), cast-iron motties tied to them showed managers which miners had hewed which coal. Miners’ pay was linked to the amount of coal extracted. A miner caught replacing another miner's motty with his own would lose his job. The miner digging coal from the coal face was a ‘hewer’ and the miner taking loaded coal tubs from the coal face to the pit bottom and bringing back empty ones was a ‘putter’.

Tipple tin (pay tin)

A designated miner would use a tipple tin to collect the wages for a number of men and distribute them from his tin. Later, numbered pay checks were introduced for miners to collect their wages with.

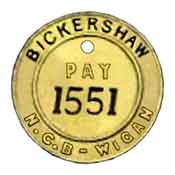

Pay check

Bickershaw Colliery pay check.

This colliery was located at Plank Ln, Leigh, on the north side of the Leigh Branch of the Leeds & Liverpool Canal, (53.49265, -2.55388).

An early shaft was sunk in 1830 but little is known about this. In 1872 work began on sinking Shaft Nos. 1 & 2 and these were followed in 1877 by work commencing on sinking Shaft Nos. 3 & 4. In 1907 work began on sinking Shaft No. 5.

Between 1973 and 1976 Bickershaw Colliery was connected underground to Parsonage and Golborne Collieries, about 1.28 miles distant (bearing NE 66°) and 2 miles distant (bearing SW 242°), respectively. Conveyor belts carried coal from them to Bickershaw Colliery where it was wound to the surface. The three collieries were known as an ‘NCB Super Pit’. Golborne Colliery closed in 1989 and Bickershaw and Parsonage Collieries closed in 1992.

Pay check & safety lamp check

Left: Pay check from Parsonage Colliery (1913/19-1992). This colliery was located in the present Parsonage Retail Park between Parsonage Way and Atherleigh Way, Leigh, Wigan, (53.49987,-2.52789).

Right: Safety lamp check from Golborne Colliery (1860s-1989). This colliery was located on the southern edge of the present Golborne Park to the west of Church St, Golborne, Wigan, (53.47923, -2.59672).

On the 18 Mar 1979 an explosion of firedamp occurred in the Plodder Mine of Golborne Colliery that caused 10 fatalities and one seriously injured survivor.

Safety lamp checks

Left: Safety lamp check, Hapton Valley Colliery (1853-1982), Billington Rd, off the west side of Rossendale Rd, Hapton, Burnley, (53.77793, -2.28798).

Centre: Safety lamp check, Parkside Colliery (1957-1993), off the north side of Southworth Rd, Newton-le-Willows, (53.45681, -2.60379). This was the last working coal mine in the Lancashire Coalfield.

Right: Safety lamp check, Hebburn A Pit (1792-) of the Wallsend & Hebburn Coal Co Ltd, off the south side of Wagonway Rd, Hebburn, South Tyneside, (54.98227, -1.50965). This pit produced ‘Wallsend’ house coal.

These checks enabled the colliery management to account for coal miners at the start and end of their shift underground. They were vital when rescue services needed to know how many men were actually underground during an incident such as a fire or explosion. Check systems became widespread during the 19th century and they became mandatory in 1913 following an amendment to the 1911 Coal Mines Act. There were a number of different systems for using them but the following is typical:

On arrival at work every miner reported to the lamp room/time office where he was issued with two personally numbered checks and a safety lamp. The miners then went to the colliery bank where the banksman was waiting to supervise them entering the cage that would take them down the shaft. Each miner gave one check to the banksman and retained the other. When everyone had descended the shaft, the banksman returned the checks he had collected to the lamp room/time office. On ascending to the colliery bank at the end of their shift, each miner handed in his check and safety lamp under the supervision of the banksman. In this way, every miner who started a shift was accounted for.

Miner’s candle holder or ‘Sticking Tommy’

In use this type of candle holder could be hooked over a timber or the point could be stuck into a timber or wedged into a crevice in the coal. It could even be stuck into a hat.

Due to the presence of flammable firedamp (methane) in mine galleries the use of candles was dangerous and candles and holders were phased out after 1815/16 when safety lamps were introduced.

Miners’ safety lamps

Left, Davy lamp and, right, Stephenson lamp also known as a Geordie lamp.

Sir Humphry Davy and George Stephenson independently invented the safety lamp in 1815/16 for the purpose of providing a safe source of light in coal mines.

The lamp allowed oxygen for the flame to get in but prevented it from coming into contact with any flammable gas present in the mine. This gas, known as firedamp, mainly consisted of methane. Air entering the lamp passed through wire gauze, the purpose of which was to cool any flame or spark escaping from inside the lamp and so prevent it from igniting any firedamp present in the mine. There was an additional advantage in that a safety lamp detected the presence of firedamp by the flame burning higher with a blue tinge.

Another notable safety lamp was Biram’s Safety Lamp, known as ‘Biram’s Patent Economy Safety Lamp’ that was introduced by Benjamin Biram (1804-1857) of Yorkshire. He is also credited with inventing a mechanical anemometer, known as ‘Biram’s Whirly Gig’ used to measure the volume of air entering or leaving coal mines.

Miners' safety lamps

Left: Safety lamp manufactured by Richard Johnson, Clapham & Morris of Dale St then Lever St, Manchester. Works at Newton Heath, Manchester.

Right: Safety lamp manufactured by W E Teale & Co Ltd of Swinton, near Manchester.

Typically, safety lamps were spirit lamps burning a mineral spirit based on naptha, such as Colzaline, Coleman liquid fuel or benzoline. They were lit either by an internal flint lighter or by applying a low voltage (2V) across a platinum filament adjacent to the wick.

Garforth Safety Lamp

This is a Type GR6S safety lamp manufactured by the Protector Lamp & Lighting Co Ltd of Eccles, near Manchester. Garforth safety lamps were introduced in the 1960s as the approved method of checking for firedamp. They are also referred to as the Pit Deputy’s Lamp.

Pit Deputy's Yardstick

A pit deputy was an underground official who was responsible for an area of coal working. The yardstick was a mark of rank within the pit and showed that the possessor was a colliery official.

Historically, a yardstick was used to measure the length of a coal seam that a miner was expected to hew during his shift. Later, yardsticks had several other uses:

It was used to measure the distance between pit props supporting the roof to check that they were set to the regulation distance apart.

It was used to detect firedamp (methane) where there was a high roof. A yardstick raised a safety lamp towards the roof level and a trained eye could detect the change in the appearance of the flame when firedamp was present. Firedamp is less dense than air and it accumulates under the roof.

A pit deputy would carry an aspirator bulb fitted with an adaptor that fitted over the brass ferrule on his yardstick. He would squeeze the air out of the bulb and then quickly raise it to the roof where it would inflate, sucking in a sample of air at roof level. The air collected was then squeezed into a Garforth safety lamp where any change in the flame could be detected.

Electric safety lamp check

This check shows that it was for use with an electric safety lamp. It was issued for use at Bradford Colliery, Manchester, by Manchester Collieries Ltd.

Effective hand-held electric safety lamps were first developed for use in coal mines in the early 1900s.

Miner's electric safety lamp

Oldham Type C battery powered safety lamp manufactured by Oldham & Son Ltd of Denton, Manchester.

This lamp was approved for use by the Home Office on the 13 Mar 1913.

Miner's electric safety lamp

Oldham-Wheat battery powered safety lamp manufactured by Oldham & Son Ltd of Denton, Manchester.

The name ‘Wheat’ refers to the inventor Grant Wheat (1884-1955) whose products were manufactured by Koehler Lighting Products of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, USA, and by Oldham & Son Ltd.

Miner's helmet, electric cap lamp & battery case

Miner's leather safety helmet

Miner's compressed paper safety helmet

These helmets were made from a pulp consisting of recycled paper, rags and/or wood pulp. This material was both strong and water resistant which made it suitable for making safety helmets. A manufacturer of these helmets was the Patent Pulp Manufacturing Co Ltd of Thetford, Norfolk, who described them as protective helmets or fibre ware helmets.

Ormerod detaching hook

Raising the miners’ cage from a mine shaft was dangerous and in the event of an overwind there were two possibilities; the cage could either be pulled right out of the shaft landing on top of the roof of the winding engine house or the rope could snap and drop the cage to the bottom of the shaft. In 1867 Edward Ormerod (1834-1894), a mining engineer at Gibfield Colliery on Coal Pit Ln, Atherton, Lancashire, solved the problem when he invented his detaching hook.

This safety device prevented the cage from being drawn past the landing stage and over the mine headgear wheels in the event of an overwind or from falling down the mine shaft if the winding rope snapped. In the event of an overwind the hook was made in such a way that it released itself from the winding rope and engine. In so doing it safely located itself in a bell-mouthed cylinder secured to the framework of the headgear. To achieve this, force from the bell onto the lower half of the hook sheared a copper pin and this opened the top portion of the hook. This action detached the winding rope from the hook which then latched itself onto the top of the bell. Once in place, the hook held the cage safely underneath thereby preventing it from falling back down the mine shaft.

Proto mine breathing apparatus

The Proto self-contained breathing apparatus is comprised of a chest-mounted canvas-covered breathing bag, oxygen cylinders, supply tubes, a nose clip, a mouth-piece and skull cap. This apparatus was developed during the Great War (1914/18) and it was manufactured by Siebe, Gorman & Co Ltd of London, who had made similar equipment for the mining industry since 1902.

1819: Augustus Siebe (1788-1872) founded Siebe & Co. 1868: Henry Herepath Siebe and his son-in-law, William Augustus Gorman, ran the business after Augustus Siebe retired. 1870: William Augustus Gorman became a business partner and the company was renamed Siebe & Gorman. 1904: Siebe, Gorman & Co Ltd was incorporated.

A problem faced by sappers digging tunnels on the Western Front was that of carbon monoxide gas which was released into the earthworks following the detonation of explosive charges. Sappers were often caught unawares because this gas is odourless and tasteless and moreover rescuers often became casualties themselves as they tried to save their comrades. To combat this hazard the most modern breathing equipment available was obtained and this was the Proto.

A self-contained breathing apparatus, the Proto recycled carbon monoxide into the chest-mounted breathing bag, purified it with sodium carbonate and with the aid of the oxygen contained in the cylinders it permitted the user to have clean air for breathing. By regulating the amount of oxygen stored in the bottles it was possible to work in a contaminated atmosphere for over two hours.

Clog bottom ('donkey' or 'horse')

Clog bottom with a groove along the underside.

To use them a miner placed a pair of clog bottoms onto the coal-tub rails at the top of an underground incline (called a brow) and then stood on them in order to slide down to a lower level while holding his safety lamp, snap tin (for sandwiches) and dudley (water bottle).

In some districts, miners wore special clogs that were hollow underneath in the manner of clog bottoms and these were used in the same way.

Dudley

A dudley is a round water container that miners took underground.

Snap tin

A snap tin is a sandwich container that miners took underground.

Tea & sugar box

This double ended box allows the storage of tea at one end and sugar at the other.

Pocket watch & brass case

Pocket watches taken underground in brass cases were considered safe as brass cannot cause a spark and ignite firedamp.

Brass snuff box

Brass cannot cause a spark and ignite firedamp.

Miners’ Welfare Institute token

This token is from the Bradford Colliery Miners’ Welfare Institute (BCMWI) on Teddington Rd, Moston, Manchester. This institute was provided for Bradford and Moston Collieries which were finally connected together underground as they were only about 2.4 miles distant from each other. This institute is now known as the Miners Arts & Music Community Centre.

Miners’ Welfare Institutes, or Miners’ Institutes, were started during the 19th and early 20th centuries as meeting and educational venues. They were owned by groups of coal miners who gave a proportion of their wages into a communal fund to pay for the construction and running of the buildings. The institutes often contained a library, reading room and meeting room. Additionally, they catered for the cultural, recreational and social life of coal-mining communities.

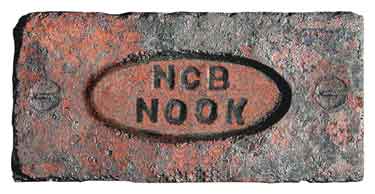

Brick made by the National Coal Board (NCB)

The brick illustrated was made by the NCB at the brick works associated with Nook Pit, Tyldesley, Lancashire. This dates its manufacture to sometime after the 1 Jan 1947 when the coal industry was nationalised.

During the workings of coal mines viable deposits of clay were sometimes discovered that were suitable for brick making and the opportunity to establish brick works at these mines was taken. The brick works at Nook Pit was situated a short distance to the south east of the pit.

Hessian coal sack

Coal sack weight tags

For fixing to hessian coal sacks for delivery.

Left: Tag issued by Manchester Collieries Ltd.

Right: Tag issued by Blyth & Nephew of Manchester. Used for 1 hundredweight of coal or ½ hundredweight of coke.

1 hundredweight = 112 pounds.

Horse-drawn coal delivery cart

Cast-iron coal hole cover

These were located in pavements outside Victorian houses where they covered the chutes through which householders had their coal delivered. Typically, they were 12 to 14 inches in diameter.

Coal purdonium & scuttle

Left: A coal purdonium, which is a wooden cabinet with a sloping front and metal lining to hold the coal.

Right: A coal scuttle. These were made in a variety of metals such as, brass, copper, pewter, cast iron or galvanised steel.

Badges of the National Union of Mineworkers

Top left, National Area Badge, & top right, Lancashire Area Badge.

Bottom left, Houghton Main Colliery, Barnsley, Strike Badge, & bottom right, County Durham Strike Badge, both for 1984/85.

Bevin Boys Veterans Badge

This badge was introduced on the 20 Jun 2007 and they were awarded to men who:

~ were conscripted directly into mines and who were generally known as Ballotees;

~ chose to do mine work in preference to joining the Armed Forces;

~ were in the Armed Forces and volunteered to become miners during the period 1943–48 under the scheme instituted by Ernest Bevin, Minister of Labour and National Service.

This badge is a survivor’s badge and applications could only be made by Bevin Boys or their widows.