An unusual feature in Joe's younger days was a tramroad, as he called it. Before the Midland Railway arrived, the inhabitants had been dependent for most heavy goods on a canal (Peak Forest Canal) that came into the hills by a winding way, and with many locks (Marple Locks), sixteen in a row up one rise, and ended at a village a little way to the west (Bugsworth). From this canal someone, before Joe was born, had conceived the idea of running a line through to another village (Dove Holes) much higher up, and to certain limestone quarries around Dove Holes. This line passed under the main street (Market St) fifty yards beyond the last houses of Townend, Chapel-en-le-Frith, not very far from Warmbrook Barn (in fact, Warmbrook Barn is about 520 yards due south).

Naturally, this tramroad fascinated young Joe, and continued to do so as he grew up, for the chief motive power was horses (in fact, horses up the tramway, gravity down it). There was a warehouse (in fact, there were two warehouses, the Lower Warehouse and the Upper Warehouse), a big yard, and a row of stables just below the main street (Market St, Townend), for it was an important unloading place for local supplies and also for several villages in a long dale to the east, which had only roads in and out. The more or less level line from the port (not so, the tramway was uphill from Bugsworth) took a sharp climb at Chapel-en-le-Frith, so steep that horses could not face it (the inclined plane).

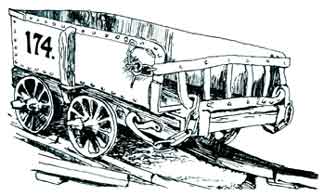

But perhaps this line is worth describing in more detail, as a record of the primitive transport (in fact, its design was ingenious) with which for 120 years Joe's, and a number of other villages, had to manage. At the port (Bugsworth Canal Basin), goods were shifted by hand cranes out of barges (narrow boats) into the tramroad trucks (tramway waggons). Each truck weighed sixteen hundredweight (in fact, ¾ ton to 1 ton) and would carry up to two tons (in fact, 2 to 2½ tons). As many as forty trucks were sometimes run together in a gang, the total weight being normally about 120 to 150 tons (in fact, 30 to 40 tons nett, 110 to 140 tons gross).

From the wharf (Bugsworth Canal Basin) the gang set off for Townend hauled by five horses in line attended by a man and youth (waggoner and apprentice), who took them the two miles to a half-way trough, where the horses were unhooked, had a drink and rested. Here there would usually be a down gang waiting, brought there of their own weight (i.e. by gravity), the man in charge (waggoner) acting as the brakeman to control the speed; or if no gang had arrived one soon would, and after it would come a boy (apprentice) from the village (Townend) with another five horses. Now the man who had come up from the wharf (Bugsworth Canal Basin) took over the down gang as brakeman (waggoner), and left the lad (apprentice) who had gone with him to return with the horses, while the man and youth (waggoner and apprentice) from the village (Townend) hooked up their five horses and took the gang forward on the remaining two miles to Townend. When the tramroad was in its heyday three gangs were taken down each day in this way and three were brought up.

At the village junction (Townend Marshalling Yard) shunting took place , those trucks for the farther villages being made up into fresh gangs, an old, wise horse being retained for this work. When a gang was ready, this horse towed it to the foot of the climb, known as 'the incline' (the inclined plane at Chapel-en-le-Frith), where the trucks were hooked onto a wire hawser (a 2-inch diameter endless steel rope). At the top of the incline was another marshalling area, another warehouse (in fact, a carpenters shop and a blacksmiths shop), and another row of stables for eight horses. This was the Top o' th' Plane. The outstanding building was the control cabin, of wood, on tall stilts, like an early lighthouse (brakeman's box). The man on duty there had a clear view of the slope, and all over the marshalling area just below him. Between the stilts was an iron wheel, ten feet in diameter (the diameter of the brake drum was 14 feet), with a grooved edge, and set on a perpendicular axle. Around the groove ran the steel hawser. When the bottom gang was ready a huge hexagonal white board on long pole was turned broadside as a signal, then the control man (brakeman) gave a sign to his mate, who removed the chocks holding back a loaded gang at the top, and over it went, its weight hauling up the gang on the other line. In fog a big bell jangled as signal. If the big wheel was spinning too fast, then the man in the cabin (brakeman) could screw a brake down on the rim and delay the wheel somewhat by friction.

Each gang was taken on from the Top o' th' Plane by a four-horse team in-line for a mile or so to another half-way point (in fact, under 1 mile from Dove Holes), the gang rolling two farther miles after that by gravity. All the horses used, twenty five to thirty regularly in the seven miles, were retired from ordinary railway delivery duties through city streets, their feet knocked up by the rough setts in those days (in fact, the horses were bred locally). When hauling a gang, they trod on earth between the narrow lines (the rails had a gauge of 4 feet 2 inches), there being no wooden sleepers, each rail being spiked onto squared blocks of gritstone (stone sleeper blocks) set firmly in the ground at twelve to eighteen-inch intervals (in fact, 1 yard). I have thought that it must have been rather nice for old horses jaded by city labour, this life along the line, for it passed three-quarters of its length through valley fields, and the remainder along the lip of a tree-deep gorge, as attractive as any in the Peakland. Certainly the men who worked the line liked their employment, for Joe says they very seldom left, and there was much disappointment when the line shut down*.

There were perils, of course. Joe often rode up to Top o' th' Plane sitting on the edge of a waggon in a gang and says he never thought anything about it then; but he has often wondered since at the risk, for he remembered the hawser snapping on several occasions, both gangs crashing down to the bridge over the tramway (at Market St, Townend). Under this bridge there was only a single line, the gangs being hooked up and unhooked on the top side. Immediately the old horse that did the assembling was released, it departed into its stable, a cave cut out of rock at the side, like an air-raid shelter (a refuge in a boundary wall). There was a similar cave (refuge) for the two men who worked at the bottom of the inclined plane, so that neither ever got struck down when waggons ran away.

Other men, however, seem to have risked greater danger every day, on the lengths where the gangs ran by gravity (the full length was gravity operated). Fully laden, they could get up great speed (the maximum allowed was 4 miles/hour but 6 miles/hour was common). The brakeman (waggoner) rode standing on the end of a waggon chassis, holding on to a waggon edge (in fact, he stood on the linchpin securing a wheel onto the axle). By each pair of wheels hung a short chain with an iron pin on the end (in fact, a 3-link chain with a hook at each end). When a gang was beginning to speed too much, the man had to bend down, and thrust this pin (throw the hook) between the iron spokes of a wheel, the wheel thus being locked (this was called spragging). Think how adroit the man had to be. Think if he slipped or lost balance, or failed to time his thrust (throw) rightly, or the chain snapped! Also it was seldom enough to brake one wheel or one waggon, and he had to move along the rocking gang to the next ····· perhaps perform the same operation on five or six waggons. Moreover, a wheel might be left skidding very long or it would get red hot and wear badly (wheels did wear badly and break because of this), so that the man had to make his way hand-over-hand, jerk the pin and peg (i.e. secure another 3-link chain to a wheel) through spokes, or trip another wheel. To release the peg (unhook the chain from the wheel) he had a short iron bar he used as a lever, but obviously there must have been considerable risk in this operation, too. Yet Joe did not recall any employee being killed, and only remembered one accident, a brakeman (waggoner) getting an arm broken. "It were great ta watch them, they could do it like snuff."

Towards the end, the Board of Trade obliged the Company to provide iron platforms on each waggon with a guard rail for the brakeman (i.e. the waggoner but there is no evidence that this was done), but the actual wheel locking (spragging) remained as perilous as ever.

Another friend, not Joe, remembered a boy, in mischief with several pals setting some waggons going and trying to peg a wheel (sprag a wheel to brake the waggons). Overbalancing or being hit, he fell on the track and was cut in two (this did happen).

The extension of the new railway line by the Midland Railway Co seriously lessened the amount of freight carried on the tramroad, and eventually made it uneconomic. When first I got to know Joe the line remained intact but dead. There was grass between and over the rails, and it was pleasant to stroll in peace where once all that traffic had run. Then eventually most of the buildings were taken down, the stone used elsewhere, the rails were removed, and only the gritstone blocks (stone sleeper blocks) were left. After more years the land was even offered for sale, and was bought in short lengths by many different persons, so that now in many places crops grow where once trundling gangs of tramway waggons passed half-a-dozen times each day.

In October 1941 I was out with Joe when he pointed to a man going laboriously on two sticks and said, "'e were th' last man as worked on th' old tramroad, 'e were there till th' lines were took up." I believe Joe added that the man had been one of the horse drivers, though I am not sure.

The last man to work the control cabin (brakeman's box at the top of the inclined plane), he did the job for thirty years, died about the beginning of the Second World War. Even in that war a part anyway of the tramway served a useful purpose. In the seven miles there was one tunnel (Stodhart Tunnel), 150 yards long (in fact, about 94 yards long), with a single track penetrating a high bluff half-a-mile north of Townend village. The length which included this tunnel was bought by a big industrial concern (Ferodo Ltd) and the tunnel used for storage of valuable papers from air attack, the ends being strongly sealed. Open again after the war, the tunnel has since been used for safe-keeping of highly inflammable chemicals by Ferodo Ltd (in fact, Ferodo used the tunnel to test brakes). But the most lasting relic of the tramway is likely to be in Townend village some distance from the defunct line. It is a strongly built, double-fronted house on a corner very nearly opposite Joe's boyhood home.

"It were built wi' sixpences," said Joe one day as we passed; and I learned that the builder had for many years been the carter at the village junction (Townend Marshalling Yard) when the tramroad was in its most prosperous period. "Th' sixpences were th' tips 'e get fer deliverin. 'e built it when 'e retired."

Appendix

This story about the operation of the Peak Forest Tramway is from one chapter of a book entitled ‘Chuckling Joe‘ by Crichton Porteous, published in 1954.

The book is a biography of a character nicknamed Chuckling Joe who lived all his life around Chapel-en-le-Frith. Chuckling Joe was Joseph Marchington who was born at Chapel-en-le Frith in 1871.

He married Alice Capper in 1899 and the couple lived on Manchester Rd, Chapel-en-le-Frith, where he was employed as a drayman at the railway station.

This description of the Peak Forest Tramway is historically important for the details it provides but it only discusses the transport of goods up the tramway from Bugsworth Canal Basin towards Townend and the inclined plane at Chapel-en-le-Frith. There is no mention of the tramway's main purpose, which was the transport of limestone and burnt lime from the quarries around Dove Holes down to Bugsworth Canal Basin.

Crichton Porteous is the nom de plume of Leslie Creighton Porteous who was born at Leeds, Yorkshire, on the 22 May 1901. It is believed that he grew up somewhere in the Manchester area and that some of his school holidays were spent in the Peak District of Derbyshire. It was in the Peak District that his love of the countryside developed and while still a youth he began writing articles about outdoor life for boys' magazines. On completion of his education he became a farm worker and after a few years of this he joined Hulton newspapers where he became a sub-editor. He then worked for several more papers before eventually becoming the assistant editor of the northern edition of the Daily Mail, which was printed in Manchester.

Following his marriage, he moved to the hamlet of Combs, near Chapel-en-le-Frith, Derbyshire, and simultaneously he resigned from his position at the Daily Mail to become a free-lance writer. His first book, Farmer's Creed, was published in 1938 but only after he had rewritten it five times. Over the next three decades he wrote about one book a year as well as numerous short stories and articles.