Authorisation, Construction and Abandonment

The Act authorising the Ashton Canal, or the Manchester, Ashton-under-Lyne and Oldham Canal to give it its full name,

received the Royal Assent on the 11 Jun 1792 (Note32 George III cap 84.).

This was, 'An Act for the making of a navigable canal from Manchester to or near Ashton-under-Lyne and Oldham in the County Palatine of Lancaster'.

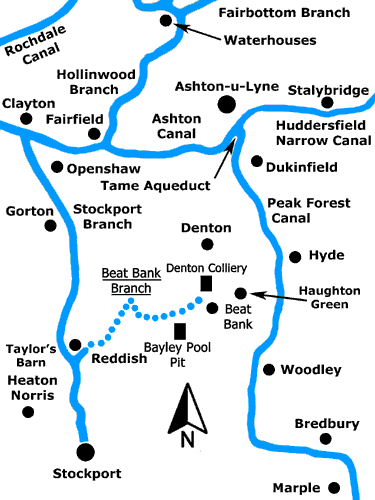

The canal was to be constructed from the eastern end of Piccadilly, Manchester, to Fairfield and from there to Dukinfield Bridge at Ashton and also to New Mill near the town of Oldham.

This Act authorised a branch canal that was planned to commence at Fairfield and be cut in a northerly direction until it reached the vicinity of the river Medlock near Waterhouses. From there it was to generally follow the southern bank of the river, upstream, (but crossing it twice) to terminate at New Mill near Park Bridge. The Act also made provision for a short branch at Ashton to cross the river Tame into Dukinfield (NoteThe Peak Forest Canal started at the southern end of the Tame Aqueduct in Dukinfield, Cheshire.).

It is evident that concerns were soon being expressed within the Canal Company about the adequacy of coal supplies for the canal to carry and thus generate income. On the 18 Sep 1792, the Manchester Mercury reported that a meeting of Proprietors was to be held to consider proposals and estimates for making branches from the Ashton Canal and the method of raising money to enable this to be done. On the 20 Nov 1792, this paper announced that a General Meeting of the Company of Proprietors would take place on the 12 Dec 1792 to consider the draft of a proposed Bill intended to be applied for in the next session of Parliament. This draft contained details of proposed extensions to the Ashton Canal.

The November press announcement stimulated new interest in the Company and on the day before the General Meeting a Notice was placed in the Manchester Mercury for the sale of shares in the Ashton-under-Lyne and Oldham Canal. Applications were to be sent to A B George's Coffee House, Temple Bar, London.

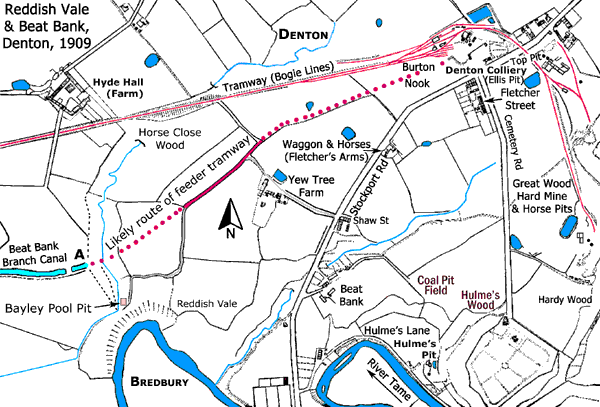

The Second Bill received Royal Assent on the 28 Mar 1793 (Note33 George III cap 21.). It authorised the cutting of a lock-free southern branch from Clayton to the Three Boars Heads Inn at Heaton Norris, Stockport, passing through Openshaw, Gorton and Reddish and this became known as the Stockport Branch Canal. It also authorised another lock-free branch canal from this, following contours along the edge of the Tame Valley, to Beat Bank, Denton, on the Stockport/Ashton road, to access collieries in the neighbourhood. This suggests that the Beat Bank Branch Canal would have terminated at or near the hamlet of Beat Bank but its actual terminus was to have been at the hamlet of Burton Nook where there were rich seams of coal.

Simultaneously, plans for the northern canal branch (authorised by the first Act) from Fairfield were substantially modified. At Waterhouses the branch was now to cross the river Medlock where, after rising through four locks, it was to divide with one branch going to Stake Leach at Hollinwood and another going towards Park Bridge following the northern bank of the Medlock upstream. The canal between Fairfield and Hollinwood became known as the Hollinwood Branch Canal, the authorised terminus being at Bradley Bent, and the branch from Waterhouses to its terminus at Fenny Field, near Park Bridge, became known as the Fairbottom Branch Canal.

However, subsequent developments sealed the fate of the Beat Bank Branch Canal. The Ashton Canal Company had a problem in that the authorised terminus of the Hollinwood Branch Canal did not extend as far as a suitable water supply or to lucrative coal pits a short distance to the north. As it happened, the canal was extended beyond its authorised terminus at Bradley Bent to end at Jig Brow, Werneth, but this extension was unauthorised.

The pit at Jig Brow was owned by the Werneth Colliery Company, which was empowered to build a canal to an existing canal provided that it was not more than four miles long. Accordingly, they built a canal, including four locks, from Jig Brow to Bradley Bent. The total length of canal built by the Werneth Colliery Company was around 1,672 yards, well below the four miles permitted. The Ashton Canal Company bought 792 yards of this at the southern end, including the four locks, and the Colliery Company retained about 880 yards at the northern end for private use, this being known as the Werneth Canal. Later, the larger Chamber Colliery Company absorbed the Werneth Colliery Company.

The Werneth Colliery Company initially consisted of a group of collieries developed by John Evans, William Jones and John and Joseph Lees and, importantly, the Lees brothers were shareholders in the Ashton Canal Company.

The Ashton Canal Company started work on cutting the branch canals as soon as the Second Bill was passed. On the 24 Sep 1793, the Manchester Mercury reported that, '···· the Company is in want of an engineer to superintend the completion of the cutting of the Canal and several branches. The cutting of the canal from Clayton to Heaton Norris (NoteThe Stockport Branch Canal.) and from Taylor's Barn, Reddish to Beat Bank, Denton (NoteThe Beat Bank Branch Canal.) is to be let in several different lengths.'

An inspection of maps and physical remains of the Beat Bank Branch Canal shows that it was, indeed, let to contractors in several different lengths. This was, and still is, standard practice in the civil engineering industry and it pays testimony to the accuracy of both the surveyors and their instruments in those early days. It is possible to stand on Ross Lave Lane, Denton, and in one direction to see a section of earthworks and in the opposite direction to see a hillside without earthworks and yet the surveyors had absolute confidence that they had got their levels right for this isolated section. From the same vantage point it is possible appreciate the magnitude of the work that would have been required of the navvies in digging or boring through that hillside.

In common with most canal companies, the Ashton Canal Company soon became cash strapped and this gave cause for concern. A special meeting was held on the 10 Jun 1795, '···· to consider the propriety of Cutting so much of the Canal, as lies between Taylor's Barn, in the township of Reddish, and Beat Bank (it being Doubtful whether it might be for the Interest of Proprietors to cut that part of the said Canal for the present).' On the 30 Jun 1795, the Manchester Mercury reported that this meeting was adjourned until the 10 Jul 1795. However, it seems that work on cutting the Beat Bank Branch Canal continued for a little while longer.

By early 1797 the main line of the Ashton Canal and the Hollinwood and Fairbottom branches were complete and the Stockport Branch Canal was nearing completion. Having ensured sufficient supplies of coal from the Hollinwood and Fairbottom Branches, the Ashton Canal Company decided to formally cease work on the Beat Bank Branch Canal built on difficult clay slopes at the side of the river Tame. They made representations to William Hulton Senior, who was a landowner and coal proprietor in Denton, to the effect that they simply could not afford to complete it.

The Canal Company then applied for a Bill to allow them to legally abandon the Beat Bank Branch Canal, after paying compensation to landowners for damage done, and at the same time raise another £30,000, half of which was to be used to pay off debts. Predictably, William Hulton Senior opposed this Bill, so the Canal Company then offered to give him the unfinished branch. He refused this offer and simultaneously tried to get the abandonment clause defeated. He failed in this attempt and the Act (Note38 George III cap 32.) was passed on the 26 May 1798.

An examination of the 1888 Distance Tables of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway Company provides some reasons for the abandonment of the Beat Bank Branch Canal. It lists two major colliery companies who extensively used the Hollinwood and Fairbottom Branches to carry coal. These were the Chamber Colliery Company, now incorporating the Werneth Colliery Company, and the Bardsley Colliery Company. By 1888 numerous pits, dating from the 18th and early 19th centuries, would have either closed or merged but, nevertheless, the Tables illustrate that the Ashton Canal Company seems to have obtained ample supplies of coal from the Oldham area to generate enough revenue and also avoid the need to raise further capital at the construction stage back in the 1790s. Arguably, the economics of successfully operating the canal was the cause of the cessation of work on the Beat Bank Branch Canal in 1795 and its abandonment in 1798 but the influence of the Lees brothers, as shareholders of the Ashton Canal Company, cannot be lightly dismissed.

Rationale for Abandonment

It is interesting to examine in greater detail the motivation behind the Ashton Canal Company in deciding to abandon the Beat Bank Branch Canal.

At this distance in time from the events this may seem a difficult task but, as military strategists will confirm, human psychology does not change. There was a huge reserve of coal in the Denton and Haughton area and

it seems that the Ashton Canal Company too easily gave up the idea of carrying any of it on the proposed Beat Bank Branch Canal. This volte-face occurred at practically the same time that they received authorisation

to do it and in so doing they lost an important source of revenue. Human thrift suggests that if coal could be carried into industrial Manchester and Stockport from both the north and south sides of the Ashton Canal,

then it would have been done. One coalfield could then have been played off against the other and lucrative deals could have been struck and tolls levied accordingly.

The received facts are:

In common with practically all canal companies, the Ashton Canal Company was cash strapped but this was the era of 'Canal Mania' and investors were flocking to put their money into such companies. But, somehow or other, they invariably managed to raise sufficient capital to complete their projects. The Canal Company wished to exploit coal reserves both to the north and the south of the main line of the Ashton Canal and their Second Act of Parliament confirms this. Curiously, they then offered to give the Beat Bank Branch Canal to William Hulton Sr in order that he could complete it for himself. This was either an attempt to deceive or to pacify. If he had called their bluff and actually completed it as a private canal could he then have carried coal on it toll free? This leaves two imponderables. Was the Canal Company genuinely anxious about future engineering problems and just how much influence did the Lees brothers actually have on Canal Company policy? On balance, after considering the relevant facts, it seems that the Lees brothers were a major influence in the abandonment of the Beat Bank Branch Canal because its completion was not in their own financial interests. The outcome of this was that most of the coal consumed along the banks of the Stockport Branch Canal was carried there from the Hollinwood and Fairbottom Branches.

The Beat Bank Branch Canal described

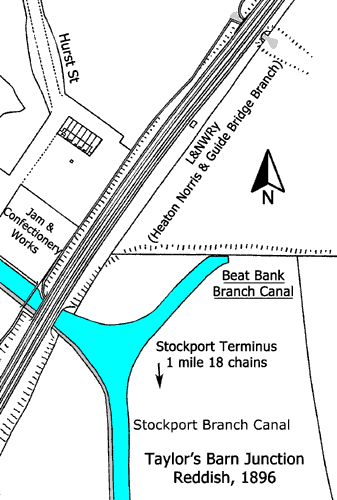

Taylor's Barn in Reddish (NoteThe precise location of Taylor's Barn is unknown.), where the Beat Bank Branch started,

was 1 mile 18 chains from the terminus of the Stockport Branch at Stockport Basin. Referring to Map 1 above, one would have expected this junction to have been further north. However, in order to follow the contours along

the river Tame, the point chosen for the junction was the only one possible.

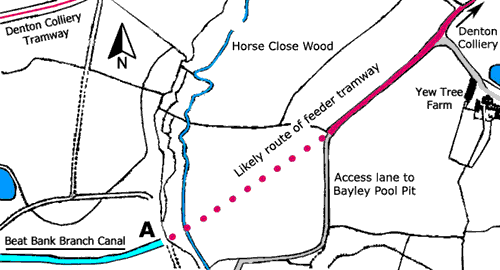

From Taylor's Barn the branch was cut for a short distance in an easterly direction before turning northwards to pass by the eastern side of Reddish Hall and then on towards Mill Lane, on the Reddish/Denton border where the cutting ceased (NoteMuch of this land is now occupied by the Reddish Vale Golf Course. It is understood that traces of the earthworks can still be seen here and at one point there is said to be a cutting, which looks as though it could have been an approach cutting for a tunnel.). The line then turned to the northeast towards Denton Wood. It then made an acute turn to the southeast to pass through the wood. A stream runs through this wood, so either a small aqueduct or culvert would have been required. On leaving the wood, the line would have passed through a cutting before arriving at Ross Lave Lane, Denton. Here there was another section of earthworks where the line turned in an easterly direction. Prior to the construction of the M60 motorway, this could still be followed along the contours to the southern end of Horse Close Wood. It seemed that all construction work on the Beat Bank Branch Canal ceased at the southern end of Horse Close Wood, where either a culverted embankment or an aqueduct would have been needed to carry the canal across the valley of the stream flowing through Horse Close Wood. However, this seems not now to be the case because there was a suspected cutting to the west of Yew Tree Farm. Following the abandonment of the canal, this final section became part of the lane leading to Bayley Pool Pit in Reddish Vale.

Beat Bank Branch Canal, Denton, 1848.

Beat Bank Branch Canal, Denton, 1909.

About 264 yards of the Beat Bank Branch Canal was completed and put into water at Taylor's Barn in Reddish

Beat Bank Branch Canal at Taylor's Barn.

Vestiges of the earthworks of the Beat Bank Branch Canal can still be seen at various places but, with the passage of time, these are disappearing. Large-scale maps show a short cutting immediately to the east of Denton Wood. This is the approach to a cutting that would have emerged near Ross Lave Lane. The earthworks adjoining Horse Close Wood were almost destroyed when a main sewage pipe was laid soon after World War II and the line can now only be identified by a row of trees. When the M60 motorway was built, huge embankments were necessary to provide approaches for the bridge across the river Tame in Reddish Vale, which resulted in more disturbance.

Even when the branch was being cut, the Ashton Canal Company was aware that the clay slopes of the river valley were prone to slippage. This process has continued ever since and has generated more loss. In the 1970s it was baffling to see earthworks at different levels until it was realised that slippage had occurred.

At that time, the local farmer, Harold Phillips of Hyde Hall Farm, Denton (NoteHarold was the brother of Ben Phillips who owned Yew Tree Farm.), said that he was aware of some 'undulations' across his land but he had always believed them to be natural features of the landscape. He was unaware that their existence had been caused by the cutting and abandonment of the Beat Bank Branch Canal.

Coal Pits at Denton and Haughton

Early maps show a number of coal pits in the Denton and Haughton areas with several being located alongside the river Tame. Where there were natural outcrops of coal,

these would have been drift mines. Hulme's Lane (Holmes Lane) provided access to these and nowadays this lane is extensively used by walkers.

Other pits were probably fairly shallow bell pits and from the bottom of these galleries would be driven into coal seam at right angles to each other so that pillars of coal were left behind to support the roof.

At some point it would be decided that the work could advance no further and the colliers would then withdraw back to the shaft and as they did so they would remove the numerous pillars of coal and in so doing cause the roof

to collapse behind them (

Eventually, some of the underground galleries would connect with those of other pits and this is how the larger pits may have emerged while others were abandoned as not being viable. There was also a need to sink deeper shafts and this required capital, especially for the acquisition of winding gear. In due time, the following larger pits emerged after the abandonment of a number of smaller ones:

Ellis Pit was on the north side of Stockport Road and Top Pit was on the south side. Denton Colliery Tramway connected this complex of pits to Denton Colliery Sidings in Reddish on the Heaton Norris and Guide Bridge Branch of the London and North Western Railway (NoteThis tramway was known locally as the Bogie Lines.).

Another interesting pit was Bayley Pool Pit in Reddish Vale situated to the south of the earthworks of the Beat Bank Branch Canal. Reference to this pit was made in an article about long-serving employees of Denton Colliery published in the North Cheshire Herald on the 28 Jan 1927.

Yew Tree Farm.

Yew Tree Farm.The Hamlet of Beat Bank

By the end of the 18th century and throughout the 19th century Beat Bank was essentially a coal-mining community but the origin of the name goes back much further.

The earliest known name for the area and hamlet is Bight Bank as it was situated on the northern bank of the river Tame. A yeoman's farm was built here and this was called Bight Bank Farm (later Yew Tree Farm).

This farm was of timber-framed construction having a stone roof and wattle and daub walls. Its appearance suggests that it was built around the time of

Elizabeth I (1533-1603) and possibly when it was first built it had a thatched roof that was later replaced by a stone roof.

An early surviving record of this farm is in an indenture dated 30 Dec 1715, which refers to Thomas Lees of Bight Bank in Denton in the County of Lancaster, yeoman. The relevant part of this document reads, '···· Samuel Torkinton of Haughton of Haughton of the same county broad bed weaver, and Martha his wife upon the second part and Thomas Lees of Bight Bank in Denton in the county of Lancaster aforesaid, yeoman, upon the third part, ····'. The 1881 Census records that the farm was 32 acres in extent and the farmer was William Whitehead, a bachelor, who lived there with his brother, Peter, a farm bailiff. The timber-framed building was demolished in 1899 to be replaced by a brick-built two-storey house that was demolished in c.1974 to make way for a new housing estate.

The hamlet was separated from Bight Bank Farm by Stockport Lane (now Stockport Road), part of the Stockport and Ashton Turnpike, and it contained miners' cottages and a farmstead with a barn and an orchard. The 1881 Census records that this farm was 45 acres in extent and that the farmer was Joseph Leather, the farmstead being known as Leather’s Fold. Shaw Street lay near the top of Beat Bank and there was a row of four terraced cottages on its southern side. Adjoining this, there was a terraced row of five cottages facing Stockport Road. Behind these there was another building divided into three parts but it is not known whether these were cottages or a workshop.

Although Beat Bank is in Denton, it lay within the ecclesiastical parish of St Mary's Church, Haughton Green, and it was without a shop or an inn. The closest inns were the Waggon and Horses (Fletcher's Arms) and the Arden Arms on either side of the river Tame. Although Beat Bank was on the Stockport and Ashton Turnpike; it must have been a very isolated community. By the late 1930s, it had been completely abandoned except for Shaw Street, the farmhouse at Leather’s Fold and a row of former miners’ cottage on Hulme’ Lane by the river Tame. The farm buildings were still in use but they were worked from Yew Tree Farm.

Origin of the Bight Bank place name

The earliest known reference to Bight Bank is 1645. By this time the Hulton family of Little Hulton near Bolton, Lancashire, owned the land and mineral rights of this part of Denton and

the rental charged to one of Mr Hulton’s tenants was, ‘···· Thomas Lees de Bightbanks, his own dwelling house 1s 4½d ····‘ (Middleton 1936, p7).

This dwelling house is possibly Bight Bank Farm (later Yew Tree Farm) because an indenture dated 30 Dec 1715 refers to a yeoman of Bight Bank in Denton in the County of Lancaster also called Thomas Lees.

The bridge over the river Tame at the foot of Beat Bank is called Beight Bridge and this was built and owned by the Stockport and Ashton Turnpike Trust.

The construction of this turnpike by the Trust was authorised by Act of Parliament, 5 George III cap 100, Royal Assent 1765.

There are several known alternative spellings for the place name and these are; Bight, Beight, Beet and Beat.

The word, Bight, in this context means, a curve in a river. A prominent feature of the river Tame hereabouts is that it meanders.

Surviving Remains

Today, practically nothing remains of the former coal pits or of the mining community that served them but with care some traces can be found. The colliery offices remain, now used as a private residence and display area for a monumental stonemason,

behind which is a fragment of the colliery retaining wall. By an Act of Parliament of 1911, it became compulsory to

have mine-rescue stations. The one built for Denton Colliery, complete with mortuary, is still extant and is now used as two private residences. One miner's cottage associated with Denton Colliery still survives,

although much altered. The Fletcher's Arms is still there but the original Waggon and Horses Inn was demolished and rebuilt. Traces of Hulme's Pit remain and have been excavated but fence posts made from iron rail that

were alongside the river have now been removed. Some drystone walls, which once formed boundaries at Beat Bank, remain and have been incorporated into garden walls. The walls flanking the entrance to the former road to

Beat Bank at the southern end are particularly well preserved and are now part of a garden wall. In Hardy Wood, a sough (drainage channel) associated with Great Wood Pit survives.

|

|

Line of the canal looking east south east from Ross Lave Lane, Denton, Aug 1981. Reddish Vale and the river Tame are off the picture on the right. |

Line of the canal looking east south east from Ross Lave Lane, Aug 1986. |

|

|

| The canal embankment viewed from Ross Lave Lane, Aug 1986. | Line of the canal looking east north east on the approach to Horse Close Wood, Aug 1981. Reddish Vale and the river Tame are off the picture on the right. |

|

|

Line of the canal looking east on the approach to Horse Close Wood, Aug 1981. Reddish Vale and the river Tame are off the picture on the right. |

Line of the canal looking west north west from the southern edge of Horse Close Wood, Aug 1981. Reddish Vale and the river Tame are off the picture on the left. |

|

Line of the canal on the approach to Horse Close Wood, Mar 2009. Reddish Vale and the river Tame are off the picture on the left. |